🌊 Inference

Where AI revenue shifts next.

👋 I’m Ivan. I write about venture capital waves.

This week’s sponsor is LaurenAI by Flippa.

LaurenAI helps you buy online businesses. Tell LaurenAI what you want (SaaS, app, ecom, content site, YouTube + budget). It returns a target list - including businesses not listed for sale, and lets you email owners from one place:

Set your criteria in 60 seconds

Get matched with businesses within your budget

Send personalised messages that actually get replies

Hello there!

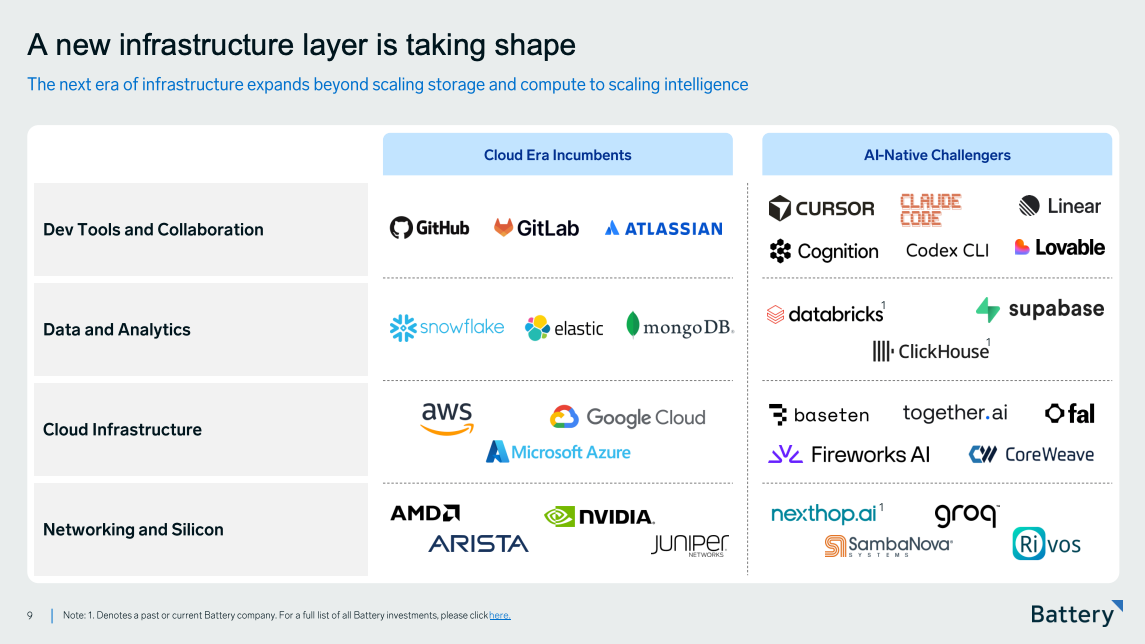

Battery Ventures published their “State of AI report”, and it answers a great question:

After training, demos, and hype, where does AI revenue come from?

The answer might be inference.

Here are my top 10 take-aways:

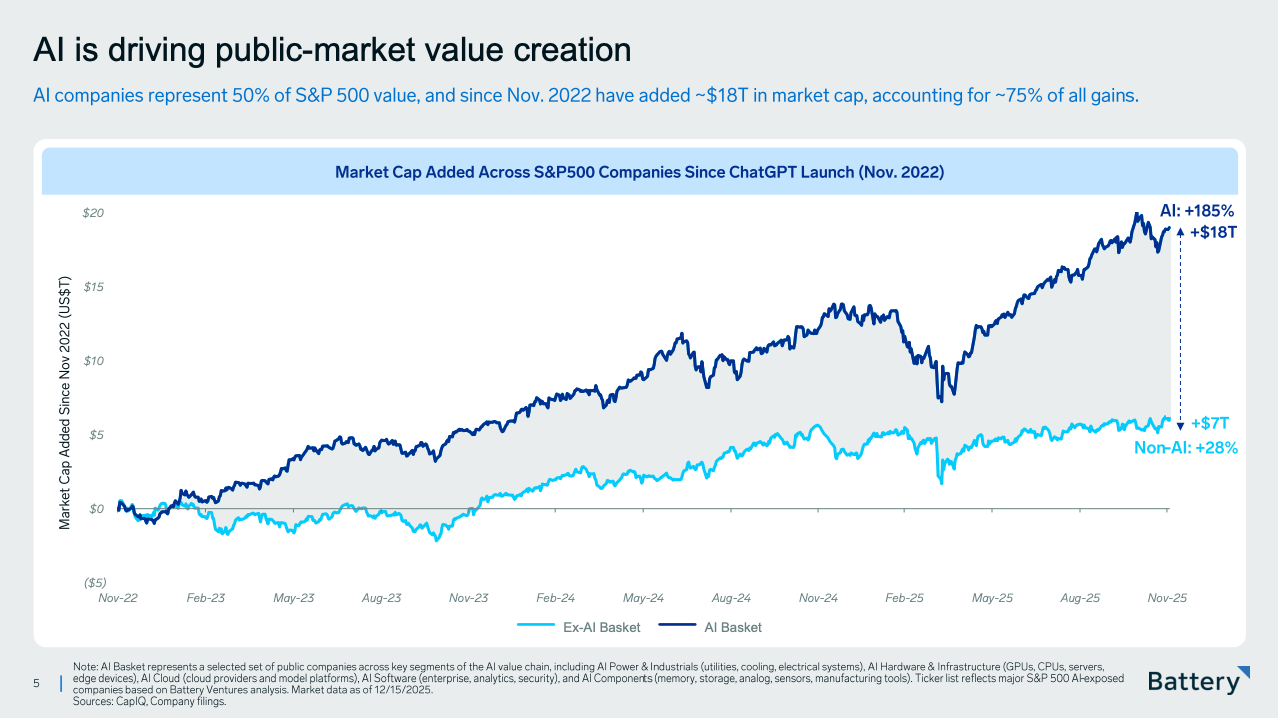

1. AI explains most of the market’s gains since 2022

The Details

Since ChatGPT launched in Nov 2022 we’ve seen AI-exposed companies adding around $18T in market cap... That is about 75% of all S&P 500 gains in the same period and are now close to 50% of total S&P 500 value.

This is not one sector winning though as it cuts across chips, cloud, power, infra, and software. Capital is basically betting on a system shift.

So what

This doesn’t scream rational investment behaviour, especially considering that the real bottleneck in AI today is power, and timelines to build this out don’t quite align with how the market has already priced this in imho (but hey, no crystal ball here).

Markets are now pricing non-AI exposure as structural risk.

Translation: if you do not benefit from AI demand your multiple compresses. If you do, you get rewarded even before margins fully show up.

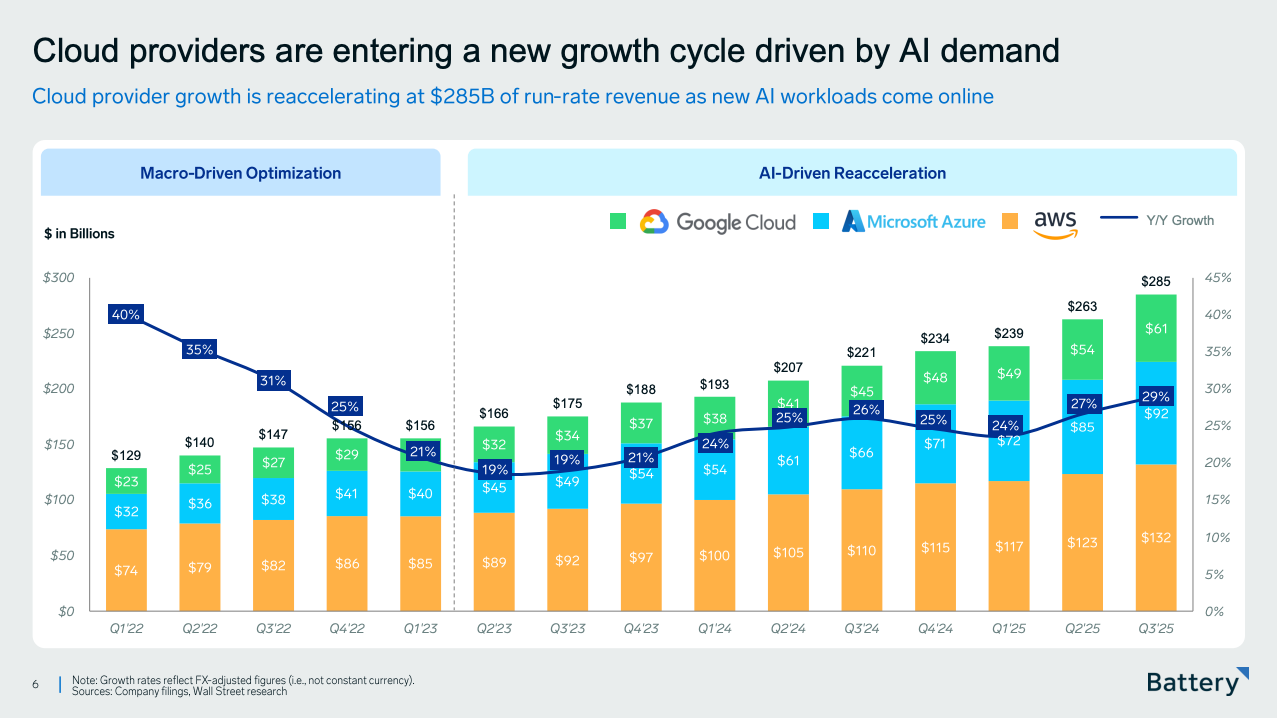

2. Cloud growth is now driven by AI workloads (not SaaS demand)

The details

After years of a little deceleration we are now seeing cloud growth accelerating to a $285B run rate (a 20% growth range).

This is basically compute-driven demand where stuff like training runs, inference calls, and agent workloads consume raw capacity. What’s interesting and different relative to the previous wave is that usage scales independently of headcount or licenses.

You see revenue grow even when customer counts do not (yet?), which again can be pointing to more fragility in the economy. That’s why you could argue that cloud itself is starting to behave less like a software platform and more like a utility again.

So what

In SaaS 1.0 we saw that growth was constrained by sales cycles and budgets but in this AI cloud wave growth is constrained by power, chips and physical infra (which explains the massive CapEx investments we explored in Accel’s research report, section 3).

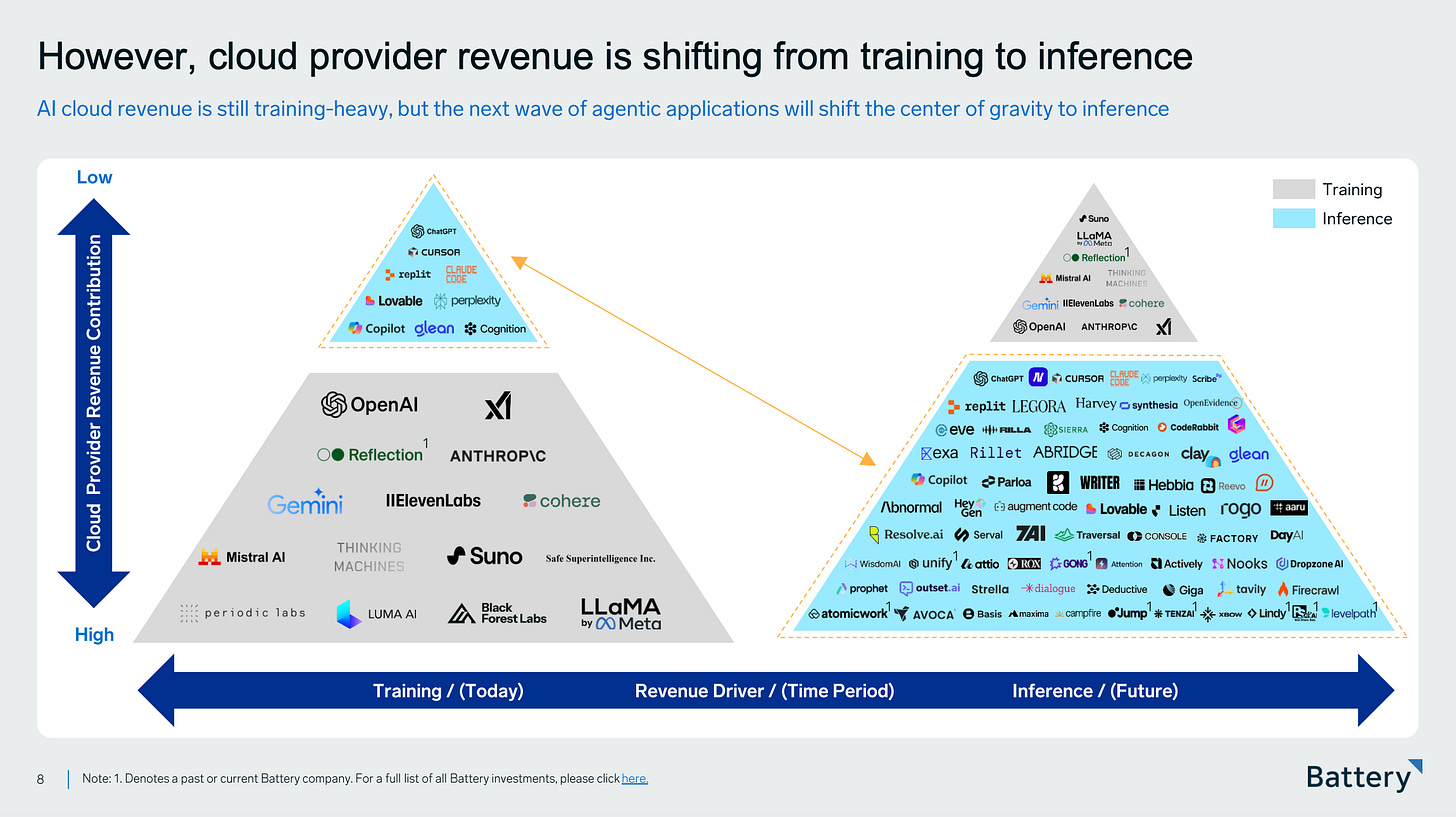

3. AI revenue is shifting from training → inference

The details

Up to now, most AI cloud revenue has come from training, which requires big bursts of compute, happens infrequently, and is tightly concentrated among a few frontier labs (what the left side of the slide above shows).

But the more interesting question is: where does revenue accumulate over time?.

As AI moves from demos into products fed into the economy the dominant workload will change because models stop being trained occasionally and start being used constantly aka inference.

Inference is every single time a model does work in the real world (i.e. answering a question, classifying a document, running an agent step, making a decision inside a workflow etc.). Each of those consumes compute and happen millions or billions of times once software is deployed.

That is why the right side of the slide looks so different, which shows that when revenue contribution broadens it spreads from a handful of model builders to a much larger surface area of companies sitting closer to usage (i.e. applications, agent platforms, orchestration tools, workflow software etc.).

There is an important piece of context here from outside this report:

In his recent conversation with Dwarkesh Patel, Ilya Sutskever (co-founder of OpenAI) made a simple but important point:

Today’s AI models already look very smart in tests but they still make basic mistakes when used in real products.

They repeat themselves, break workflows, or fail in edge cases.

Making models bigger helps a bit but it no longer fixes this reliably.

In simple terms, we may be approaching the limits of what this current training recipe can deliver quickly.

The hard part is no longer teaching models more facts but getting existing models to work reliably, cheaply, and continuously inside real systems. That includes better runtimes, better routing, better monitoring, better integration with software, and better economics.

That work happens during inference.

And even if a new architecture eventually replaces today’s models, this doesn’t really change the picture. Any future system still has to be deployed, it still has to run inside the economy, and every time it runs it is doing inference.

So what

The companies that win in an inference-led world are not just the ones that build the smartest models but the ones that make AI usable at scale. The ones that control how models are called, combined, monitored, priced, and embedded into workflows.

This is what I was trying to get at last week with the Systems of Action wave.

Once AI systems are expected to run real work, value shifts to whoever controls how actions are triggered, routed, constrained, and audited inside software.

4. Early AI leaders are no longer staying neatly in one layer of the stack.

The Details

Model companies push upward into applications and application companies pull infra-like capabilities closer to themselves.

Once AI systems run in production the hardest problems are no longer about model quality but about operating the system day to day like controlling costs, handling failures, routing work, enforcing rules, etc.

Those problems tend to sit between classic infra and classic apps.

This is where incumbents and newcomers start to collide. Incumbents like Salesforce, ServiceNow, Microsoft, or SAP already sit inside workflows and have trust, distribution, and enterprise relationships. But their stacks were built for humans in the loop and not for autonomous systems acting continuously.

Newcomers are more willing to redesign this layer from scratch building products around inference-first assumptions, usage-based economics, and AI running without constant human supervision.

So what

This creates a narrow but important battleground:

1/ Incumbents have position but architectural baggage.

2/ New entrants have cleaner designs but must earn trust and distribution.