🌊 Hidden Economics of the AI Boom

AI infrastructure bottlenecks, economic risks, and the real limits of the current AI boom.

I’m Ivan. This is a weekly founder-first market intelligence brief. A faster way for founders & investors to understand startup markets.

This week’s sponsor is AI CRM Attio:

Attio is the AI-native CRM for the next era of companies: Connect your email and calendar, and Attio instantly builds a CRM that matches your business model.

Instantly prospect and route leads with research agents

Get real-time insights from AI during customer conversations

Build powerful AI automations for your most complex workflows

Hello there!

It has been a massive quarter for AI, with a record breaking number of >$100M deals (the list of 40+ deals + 3 dominant categories here). So massive that I keep thinking about historical parallels to what might be (really) going on in our economy.

So, on this very topic, I ran into this must listen interview between Paul Krugman (Nobel-winning economist, NYT) and Paul Kedrosky (investor, MIT research fellow, long time tech + markets nerd).

It is one of the most contrarian and interesting conversations I’ve come across.

Here are the top 10 insights + my 2 cents:

1. The AI boom looks a lot like Dutch disease

What happened:

Krugman and Kedrosky frame AI as a classic “Dutch disease” story.

The details:

Dutch disease is what happens when one sector gets so hot that it quietly starves everything else of capital and attention. In the 70s, Dutch gas exports pushed wages up, strengthened the currency, and made every other industry less competitive. The gas boom was real but it hollowed out manufacturing because capital, talent, and policy chased the “easy returns”.

We see capital, talent, and political focus are being sucked into this one AI vertical today. I see it every time I talk to founders, LPs, VCs, banks, you name it (to the detriment of those building “outside” of being a “pure” ai company, for now).

So what:

When an economy gets Dutch disease founders don’t feel it as a “macro phenomenon” but they do feel it as harder fundraising, more hype expectations (as you’ve probably listened to in a most vc podcasts…) and less (perceived) room to build outside the narrative.

2. We already burned through the Saudi Arabia of data

What happened:

Transformers worked so well because we discovered a giant free data reservoir: the open internet.

The details:

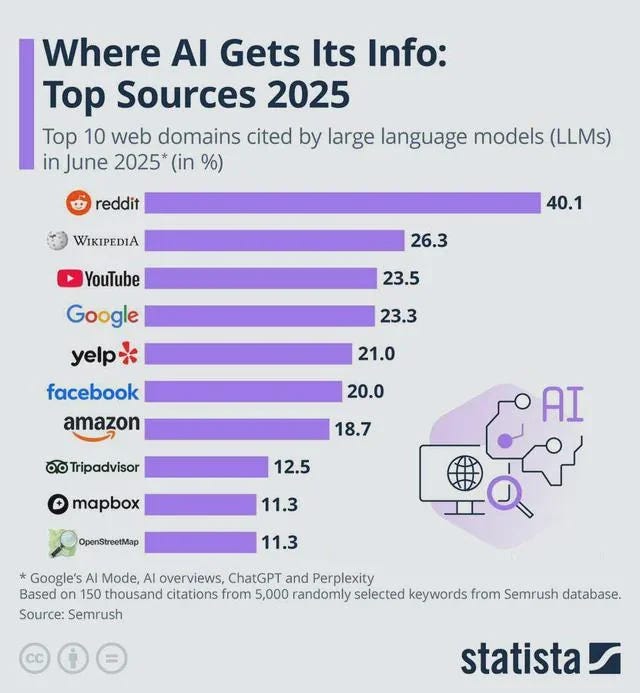

Large language models got good by training on public text at internet scale. Once we found a way to turn raw text into predictions, scaling laws kicked in: more data, more compute, better models. That trick got us from “this is a cat?” to GPT 5 level systems today. The problem is that most of the high quality public data is now used and new gains need way more work for smaller jumps. There’s a must watch interview on this topic by Ilya (co-founder of OpenAI) on this topic which I summarised here.

So what:

The easy part of the curve is behind us and it looks like the future progress is less “just add more data” and more “we need new sources, new architectures, and smarter training”. Which (might be?) slower and potentially more expensive.

3. LLMs are great at code, less great at the rest

What happened:

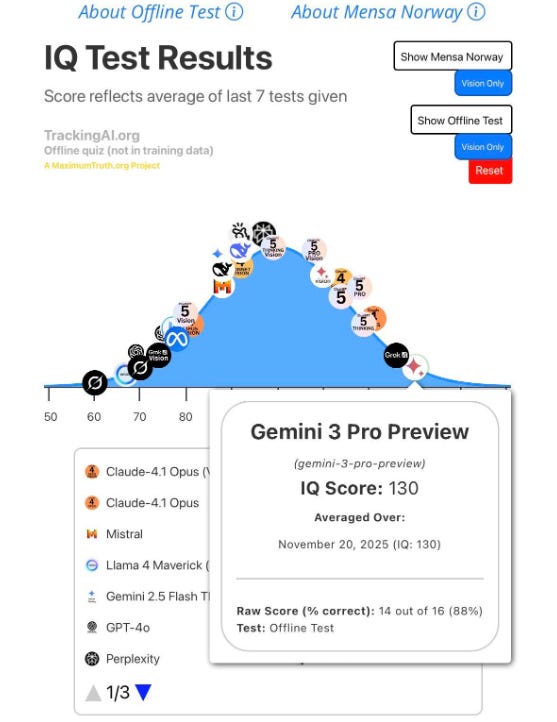

Kedrosky is very skeptical that current LLMs are on a straight road to AGI.

The details:

Models are incredibly good at software because code gives a sharp learning signal. Natural language is fuzzy: you and I can disagree on which sentence is better. So the model learns much faster from code than from prose. Benchmarks that show models “crushing coding tasks” can mislead people into thinking we are close to general intelligence. Kedrosky argues that we are not and that we are close to “very good stochastic programmer”.

So what:

Betting on AI to keep eating software workflows (and in some sectors, parts of labour) is far more realistic than betting on near-term “god-level intelligence.” LLMs have clear strengths (i.e. code, text, structured tasks) and clear ceilings. The architecture is biased toward certain domains and plateaus in others.

4. GPUs age like fruit, not factories

What happened:

The chips inside AI data centers do not behave like normal industrial capital.

The details:

Training runs keep GPUs at full throttle, 24/7, under heavy thermal stress. That is not like your laptop but more like running a race car flat out all season. What ends up happening is high early failure rates, slowdowns, constant replacement etc etc.

Which means that in a 10,000 GPU data center you should expect regular failures every few hours. Which means that long before “the next generation chip” arrives, a lot of your fleet has already worn out.

So what:

AI infra is not laying railroads you can use for 50 years (there’s been a lot of analogies on this lately). It is closer to a warehouse full of bananas, which matters for depreciation, returns, and how fragile the whole buildout might be.

5. Power (not compute) is the real bottleneck

What happened:

We are hitting the limits of the electrical grid faster than the limits of model size.

The details:

Data centers want hundreds of megawatts and even gigawatts of power. These need the kind of power normally reserved for aluminum smelters or small cities. The problem is that the grid was never built for this. Substations are full, transmission lines take years to approve and local communities push back when they hear “your bills might go up.” So utilities do strange things:

speculate on power for future AI sites

cancel projects when the demand slips

push hyperscalers into “bring your own power” deals

slow-roll approvals because the grid can’t move at startup speed

Which ties into the broader idea of fragility in this boom, because the physical world moves slower than the hype cycle.

So what:

You can raise a billion dollars in a quarter but you can’t build a gigawatt in a quarter and if your AI forecast assumes infinite, instant electricity, you are not modelling reality. It is basically modelling a wish, and this makes the economy more fragile.